Review: Reading My History Through “American Sutra”

When I was a pre-teen I found out that my father had been born in an internment camp. This information was new to me. My father never talked about how my family had been imprisoned at Heart Mountain WY during the war. When I asked about it, my dad told me, “I was an infant; I don’t remember anything.”

Once I heard my uncle talk about how he remembered the guards with guns. I would think about what life had been like for my grandparents, for my aunts and uncles, and for my infant father. From other sources I learned about the resilience of Japanese Americans during the war. I learned about the art that came out of the interment camps. I learned about the 442nd. And I felt the dignity and courage of those living through that time. But one dimension I hadn’t considered was how Buddhism lived in the camps and through the war.

Duncan Ryuken William’s book, American Sutra: A Story of Faith and Freedom in the Second World War, brings this aspect into clear focus. To be an American meant (and still means) to be Christian. The role of religion in the treatment of those deemed “other” is not trivial. It certainly wasn’t for the Japanese Americans during World War II. Why hadn’t this occurred to me before? It seems so obvious now, but it took William’s book to lay it out. Williams gives us the stories of those who were not only un-American by race, but un-American by religious belief and practice. The research that informs American Sutra is vast and intimate. And within the pages of this book the stories of my family became real to me.

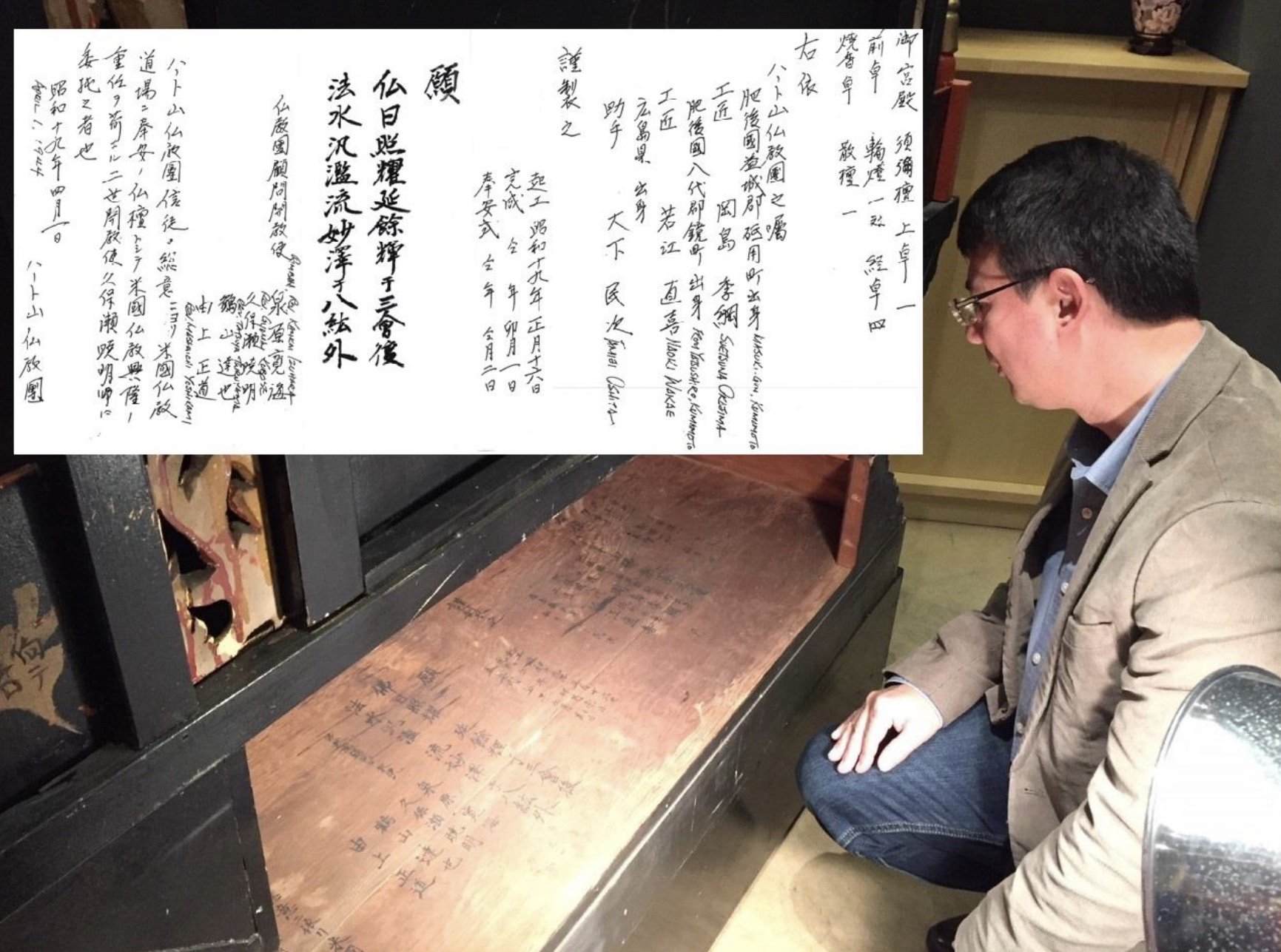

My paternal family was not only Buddhist, but my grandfather was a Higashi Honganji Buddhist priest. My grandparents had come from Japan for the purpose supporting Buddhism in American. What I learned from American Sutra was how my grandfather kept Buddhism alive right there in the middle of the war. Masamichi Yoshikami brought Buddhist books and a mimeograph into the Pomona Assembly Center before he and his family were shipped to Heart Mountain, determined to continue severing his sangha. While in Heart Mountain, along with priests from other Buddhist sects, he contributed to a large alter in the camp which still exists to this day. (Now residing in Chicago.)

Though Higashi Honganji Buddhism was foundational for my grandfather and grandmother, I knew nothing about this type of Buddhism growing up. Oddly, however, I was raised with the Dharma by my white mother in the form of Vipassana meditation. In more recent years I’ve been heavily drawn to Mahayana Buddhism, and have started researching the Pureland Buddhism of my ancestors. I don’t know what my ancestors would make of this mixed-raced, mixed-Buddhist of theirs — a queer, politically radical Buddhist who knows so little about them, but who indisputably feels the Dharma alive in her heart. Though I’m only just beginning to explore my relationship to my ancestors, William’s book has helped me feel more connected to them and to the Dharma my grandparents helped keep alive through the war years.

My family’s story is just one in a wealth of stories excavated by Williams. Collectively, these stories open up conversations into the roots of this country. As we are currently seeing parallels in interning, detaining, and imprisoning people due to their un- American-ness, this book reminds us how we bring all of ourselves to the struggle and how we must fight for all parts of who we are.

4 WAYS TO TAKE ACTION:

Related Upcoming Events, via Tsuru for Solidarity

Sign the Petition — Tell the Nakamoto Group to end their deadly ICE contract

Oct. 26th, San Francisco CA — Bay Area gathering of Tsuru for Solidarity

Nov. 16th, Oakland CA — Butterfly Effect Youth Rally to Support Migrant Children

June 5th–7th, 2020, Washington, DC — National Pilgrimage to Close the Camps